There are certain places in the world where the diamond trade was heavily tainted by a very evil force. Terrorist groups in these areas waged a gruesome war over the diamond-rich land. Under horrible conditions, these groups forced the locals to mine the stones which they used to fund armed conflicts and rebellions against the government. With no limits, they tortured the people and developed a very prosperous illicit trade of diamonds. It happened primarily in the Ivory Coast, Angola, Liberia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sierra Leone.

Though Sierra Leone’s diamond industry may have once had the potential of creating many jobs and opportunities, it was among the cause of one of the largest civil rifts in modern history. The situation got so bad that diamonds sourced from these areas were nicknamed ‘blood diamonds.’ Human rights movements from around the world came together to fight on behalf of the people that simply weren’t able to fight for themselves. At the end of the 20th century, the South African countries that were legitimately trading diamonds decided to join the fight as well. They began tracking the origin of all rough diamonds, and eventually developed what is known today as the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS). The goal was an international effort to eliminate the trade of conflict diamonds and rebuild the legitimate name of diamond trading. Everyone did their part to stop the terror, and success was seen.

Now that the war has ended and the world is very wary of controversial diamonds, some people from these areas have returned to the life of a diamond mining. In the aftermath of war it isn’t an easy task, but in countries like Sierra Leone where the unemployment rate is so high, diamond mining provides a form of livelihood.

Hence, when we noticed this story of Philo, a diamond miner from Sierra Leone, we felt it was definitely worth sharing.

Philo from Sierra Leone

Philo is a miner from Sierra Leone who has worked in Kono, the northern district of the country, for many years. As a result of the heavy conflict that plagued his land, Philo was forced to flee to Guinea, where he lived as a refugee until the war calmed down. In the year 2000, he returned to his homeland and a year later to mining.

Miners and Their Tools

Philo explained how alongside the large South African-run mine, Koidu Holdings, many artisanal miners reside along the riverbanks. While the diamond giant uses sophisticated machinery to pierce through the kimberlites with ease, allowing diamond-dense areas to be instantly revealed, the artisanal miners like Philo use sieves, spades and buckets. The lucky few who can afford a “rocker,” which is essentially a power hose, use it to efficiently clean the pile of mud and uncover any diamonds with greater ease. Philo is not one of the lucky ones and relies on sieves (or shakers as he calls them), spades, and buckets. To put things into perspective, a simple sieve goes for 25,000 Leones, which is about $4.20.

Teamwork

Like most artisanal miners, Philo works in a group of three. Each group member has a specific job that gets rotated throughout the day. One member dives into the river with the bucket in order to scoop up mud from the riverbed while a second holds him down so that the tide won’t pull him away. Lastly, the third member of the group gathers the bucket and pours it into a pile. After enough mud has been collected, he begins to sift through it in search of diamonds. The three take turns with each job so that no one gets too cold.

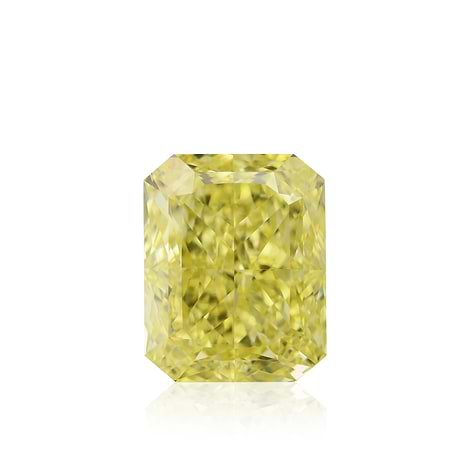

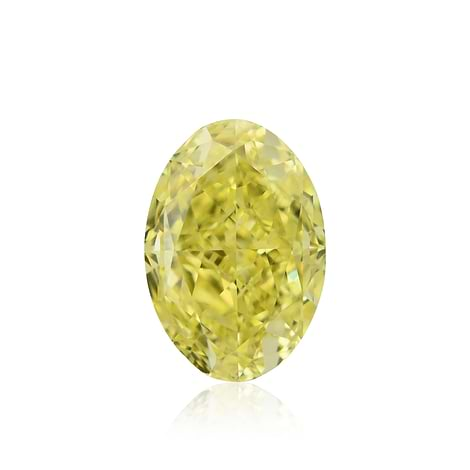

Discovering a Diamond

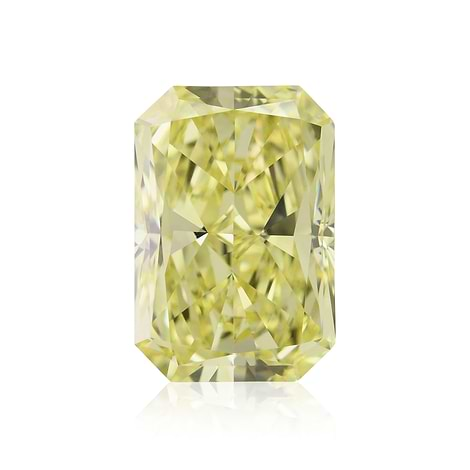

Philo’s team works while surrounded by similar groups, all in search of the glittering stone that will put food on their tables. He told about after not finding a diamond for almost a month how one day he discovered a small stone after only three hours of work. Diamonds go for approximately $3,200 a carat if they are 40% pure and much less if they are not. Philo pocketed $35 for that find, which may not seem like a lot, but is far more than he had expected. He expressed how happy he was with the find as it provided him with some well needed funds that month.

Philo shares him home with his uncle. Before the war, he lived there with his mother, but she was killed by the rebels and the house was burnt down. The house was since rebuilt and Philo returned to his childhood home in order to go back to his craft and try his luck and skill at the banks of the river. No one will deny how tough it must be, but people like Philo are willing to give it their best shot. These days, diamond mining is one of the few professions these people can do and make enough money to survive.

The terror that was inflicted upon those people was worse than one might imagine, since even though the war is over, the stink of blood diamonds still exists. Needless to say, those in the industry do whatever possible to ensure they only deal with legitimate goods. What is even better is the diamond conglomerates who have taken it upon themselves to improve the life of these miners. Their contribution is recognized by both the trade and the communities. Though it is a rough situation, it is warming to know that there is light at the end of the tunnel.